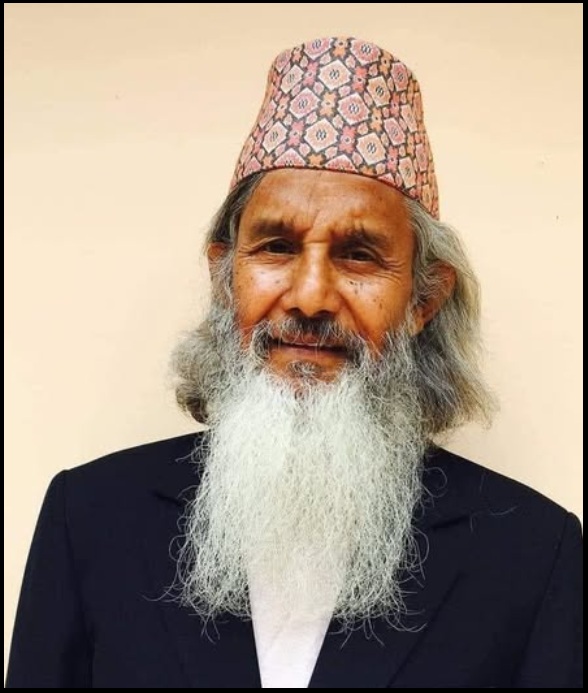

RC POUDYAL: A MUCH FEARED MAN

By Dr. Satyadeep S. Chhetri

It has been a year that RC Poudyal passed away. After his brief disappearance and an exhaustive search, his body was eventually discovered across the border in Bangladesh, washed ashore by the river Teesta. The body was mutilated and near unrecognizable due to its long exposure to water . But the watch on the wrist and his hair helped the family confirm it was him. A man once so familiar to everyone had, in death, become almost a stranger. And perhaps that was RC Poudyal’s final message. If people abandoned critical thinking or surrendered their minds, the day was not far when the very idea of Sikkimeseness will be mutilated beyond recognition… just like his body.

It is interesting to see that Ram Chandra Poudyal’s name or RC as he was lovingly addressed as , finds only fleeting mentions in the accounts of Sikkim’s transition from a sovereign kingdom to a state within the Indian Union. There could be several reasons behind this. But at best we can at least list out two reasons. One, he never chose to tell his story and two, the establishment never wanted his story to be told. Yet, despite this obscurity, RC Poudyal wielded a quiet, undeniable influence …a soft power of sorts until his final days. Politicians, both seasoned and new, held him in either deep respect or were utterly cautious when dealing with him. Even though he had renounced active politics for more than nearly two decades before his death in July 2024, his presence was at times unsettling for many. Among the general public, especially the young ones, he remained largely unknown… a distant figure. And yet, he towered over many of his contemporaries in terms of political stature.

So, who was RC Poudyal ? Who was this the man who commanded such reverence that at times I feel that even the Indian government seemed to fear this man. The answer may lie in two possibilities. One, he was a political maverick, capable of dismantling dominant narratives single-handedly. And two, he was totally unpredictable and had a mind of his own. All said and done, now that he is gone and that he did not leave his story in his own words… we may be at liberty to make analogies or at least dissect his way of life and his politics.

So, let’s return to the central question—Did the Indian Government truly fear RC Poudyal? It seems improbable that a vast and powerful nation like India would fear a single individual. And yet, during the critical years surrounding Sikkim’s merger and even in the immediate years that followed, there were moments when the Indian establishment appeared to tread cautiously around him. Certain actions by diplomats and intelligence officials suggest an effort to avoid direct confrontation with RC Poudyal. In this article I will outline at least four such instances.

The first such instance occurred during the passage of the Government of Sikkim Act, 1974. RC by then was already a newly elected legislator of the Sikkim Assembly. While many, including members of the Government officers and the enlightened Civil Society , voiced concerns, it was only RC Poudyal and NK Subedi who had the courage to sit on a hunger strike in protest. Their principal objection was with Clause 24(1), which referred to the head of the Executive Council as ‘Chief Minister’ instead of ‘Prime Minister’ for a then sovereign country like Sikkim. It carried significant political symbolism. However, their dissent went deeper. Other provisions, such as Clause 24(3) and Clause 29(2), placed India’s decisions above those of the Chogyal or the Executive Council, raising serious questions about Sikkim’s sovereignty. Most alarming was Clause 30(c), which called for the “participation and representation of the people of Sikkim in the political institutions of India”. This was a phrase that clearly signalled the move toward Sikkim becoming an ‘Associate State’ of India. This interpretation proved prophetic with the promulgation of the 35th Amendment to the Indian Constitution in September 1974, which formalized Sikkim’s altered status. RC Poudyal seemed to have sensed this political shift and opposed the bill with unrelenting conviction. Yet, instead of confronting him and the protestors directly, the government chose a quieter path. The Assembly passed the bill late at night, under tight security arranged by Indian authorities. Despite the protests, the Government of Sikkim Act was passed and received the Chogyal’s assent on July 4. It was formally notified under Notification No. 35/S.C. The rest, as they say, is history. Despite all these confrontations, RC Poudyal went on to serve as the Deputy Speaker of the Sikkim Legislative Assembly (1975–77), and later as the Minister for Forest and Tourism (1977–79). One can’t help but wonder… would such a thing be possible in today’s political environment? Would a dissenting voice be given that kind of space in contemporary politics? The answer is obvious. What now becomes increasingly apparent is a fact that the establishment wanted to keep him busy and entangled him in the day to day affairs of the state rather than allow him to remain outside the system where he could pose a greater challenge to both the Government of India and the political order in Sikkim.. The question that immediately comes to my mind is – Did ‘they’ fear him?

The second instance occurred during the crucial year of 1975, as the merger of Sikkim with India was underway. A particular incident during this period dramatically altered the course of events and accelerated the merger process. It involved an attack on RC Poudyal by palace guards. The confrontation happened when Poudyal and his supporters clashed with the Chogyal’s security guards at Rangpo. The Chogyal was returning from Kathmandu after attending the coronation of King Birendra Bir Bikram Shah. Allegedly, during that visit, he had held informal meetings with some Chinese diplomats and also gone on record in the Nepalese press. This had deeply unsettled many in the power corridors of New Delhi and even in Sikkim’s political circles. To protest, RC Poudyal and his partymen had gathered at Rangpo, waving black flags as the royal convoy entered Sikkim. Tensions quickly escalated, and in the scuffle that followed, Poudyal’s hand was slashed allegedly by a khukuri wielded by members of the Sikkim Guards. Some, however, speculated that the entire episode may have been orchestrated by Kazi Sahab and his camp to serve a political purpose. Yet, no concrete evidence ever emerged to support these claims.

In one of his essays – ‘We need to free Poudyal of the Desh Bechua tag’, Jigme N Kazi writes about the whereabouts of RC Poudyal during that time followed by his absence during the merger of Sikkim with India in 1975. He writes- ‘Under the pretext of giving him proper medical treatment Poudyal was kept in an army hospital in Libing, Gangtok for some time under strict surveillance and was later (after about a month) taken to Pune in Maharashtra for further treatment by army personnel. Poudyal reveals that after Sikkim’s crown prince, late Tenzing Namgyal, came to see him at the army hospital (in Libing) and assured him of ‘working together for the cause of Sikkim and Sikkimese people’ he was taken in an army vehicle the next day.

‘No one, including myself, knew where I was being taken. Even my family members did not know of my whereabouts,’ says Poudyal while recalling what really took place during this crucial period of Sikkim’s history’. He further writes – ‘… He was released from the hospital after minor physiotherapy treatment only after Sikkim formally became an Indian State on 16th May, 1975.’

This simply meant that during the entire process of resolution of the Sikkim Assembly on April 10th 1975, the “Special Poll” held on 14th April 1975 (later termed as Referendum) and the adoption of 36th Amendment of the Constitution of India by the Indian Parliament on 26th April 1975, Ram Chandra Poudyal was not there in Sikkim. Rather he was supposedly undergoing treatment in an army hospital (probably AFMC) in Pune, Maharashtra under strict surveillance. I often wonder what must have gone through his mind during that time. I wish he had written a memoir or spoken more openly about those days, but that never happened. His struggles, his sorrows, his emotions, and his unwavering passion will remain untold. But then a bigger question still looms large… Was the establishment wary of RC’s presence in Sikkim during that time that he had to be kept away? What did they fear?

The third instance was RC Poudyal’s meeting with India’s newly elected Prime Minister, Shri Morarji Desai, in 1977 or 1978. When Desai assumed office, efforts were made from Sikkim to re-establish dialogue with the Indian leadership. It is well known that, following a meeting at Rai Cottage in Arithang and in consultation with the Chogyal, NB Khatiwada (President of the Sikkim Prajatantrik Congress) carried a memorandum to the Prime Minister. The letter explicitly called for a review of the prevailing situation in Sikkim, referencing the 1950 Indo-Sikkim Treaty of Peace and Friendship as the guiding framework. This famous meeting is a well-known fact.

But what is not well known is that, around the same time, RC Poudyal, along with JB Pradhan and BP Kharel, also sought a meeting with Prime Minister Morarji Desai to raise concerns related to the Nepali community of Sikkim. They initially approached LD Kazi, who was in New Delhi then, hoping he would help them secure an appointment with the Prime Minister. However, Kazi Sahab discouraged them and soon left for Sikkim. Undeterred, the trio went to the residence of Sikkim’s lone Member of Parliament , CB Chettri (Katwal), only to find his flat locked. Assuming he had fled the city, they made their way to the New Delhi Railway Station to look for him and to their surprise they actually found him there with an attaché box, ready to flee New Delhi. They convinced him to return and help arrange the meeting with Morarji Desai. When they finally met the Prime Minister, the conversation took an unexpected turn. The PM reportedly dismissed them and told them that they were ‘foreigners from Nepal.’ This remark provoked an immediate and sharp response from RC Poudyal. He boldly retorted that even a Gujarati could be considered a foreigner, since their historical roots trace back to Persia. In today’s political climate, it’s hard to imagine any leader from Sikkim speaking to a Prime Minister with such defiance. Yet, despite the tense exchange, RC Poudyal and his companions managed to convince Desai to look into the issue. At one point during the conversation, Desai even enquired- ‘is Poudyal a Bhutia?’ This hilarious anecdote was later recorded by former Chief Secretary and Advisor to the Government of Sikkim, Keshab Ch. Pradhan, in a memoir “Ram Chandra Poudyal as I know him.” Following the incident, Prime Minister Morarji Desai even visited Sikkim and it is believed that he met RC Poudyal during official meetings and at a formal dinner. Remarkably, the entire episode seemed to fade from public memory, as if it had never occurred. But consider this – if such an incident were to take place in today’s political climate, could it so easily be swept under the rug without any disciplinary action? Especially given that by then, Kazi Sahab had joined the Janata Party. Would a sitting Chief Minister belonging to the same national party tolerate such a breach of discipline within his own ranks? The answer here too is obvious. However, the question that looms large is – did the Indian Government fear a backlash if Kazi Sahab reprimanded RC Poudyal? Did they fear him?

The fourth instance is that defining moment when RC Poudyal had filed a case against the disproportionate seat reservation in the Sikkim Assembly and had called the Bill No 79 of 1979 as the ‘Black Bill’. He had rightly coined this term and had single handedly brought a traction among the masses even after a strong “Desh Bechua” tag that was assigned to him by NB Bhandari and his Parishad members. But it is interesting to note how the entire process of this case took more than a decade to finally read the judgement on 10th of February, 1993. Between the filing of the case which was transferred to Supreme Court in 1982 to the date of judgement, two assembly elections had already happened in 1985 and 1989. 12 long years is not an easy wait. And interestingly there was an uncanny silence all through within the ranks of the political disposition in Sikkim. The alibi for the silence being a newly learnt word, yet much used – Sub-judice. The delay seemed to be deliberate as there were just – tarikh pe tarikh – as not many new documents were placed in later hearings in the Supreme Court. The delay was so long drawn, that it took more than four years just to scribble down the judgement order by the five Honourable Justices of the Supreme Court after the last hearing. A detailed account is written in my book Sikkim: Autocracy to Half Democracy. So, the question that looms large once again is why did the Honourable Supreme Court of India keep the case hanging for so long? What did the judgment achieve finally other than shatter a vibrant politician who had been fighting for the majority of the Sikkimese populace? This long delay had silenced him so much that after losing the battle in the Supreme Court he was silenced for a lifetime. In fact, his absence during the discriminatory imposition of Income Tax only to the Sikkimese Nepalis later in the same year in 1993 was visible. He perhaps refused to stand with the same group of Sikkimese Nepalis (backed by their powerful political masters) who had celebrated his loss at the gates of Rangpo forgetting the fact that RC was actually fighting a lone battle on behalf of the entire Sikkimese Nepalis and the elusive “Nepali Seat” for the majority of Sikkim.

Keshab Ch. Pradhan further writes in that memoir- ‘Poudyal did try his best to revive the reservation of seats for the Sikkimese of Nepali origin but by then Sikkim was a divided house and things did not turn out as he wished though it was just a claim. The Sikkimese of Nepali origin will realize the folly as the days roll by. It was sad that the people of Sikkim did not rally around him when he wanted to set the injustice right. Even in later years he continued his crusade but none rallied around him and when what he said was too political to swallow and they took him as a recluse. We will leave it to history to judge him.’

I wouldn’t like to dwell into the merits of the case, but I must question the motive behind the inordinate delay in delivering the judgment. Was there a deliberate design behind this postponement, or was the delay somehow justified? What would happen if the hearing and judgement was fast tracked especially considering Sikkim’s status at that time as a newly integrated state within the Indian Union? Was the establishment wary that an early judgment could provoke RC Poudyal going into a political warpath against that judgement? What or why did they fear him?

Now that he is gone these stories will never be told. And yet when we look back, we can well ascertain what hid behind his smiles and laughter? Was it RC’s way of satire on the political ecosystem and social structure of Sikkim? We will never know. RC Poudyal was neither a flamboyant character nor did he have money and muscle to back him but I am sure he knew well that the establishment was cautious while dealing with him. He was a certainly a MUCH FEARED MAN.

(The views expressed in this article is personal. He can be reached at satyazworld@gmail.com)